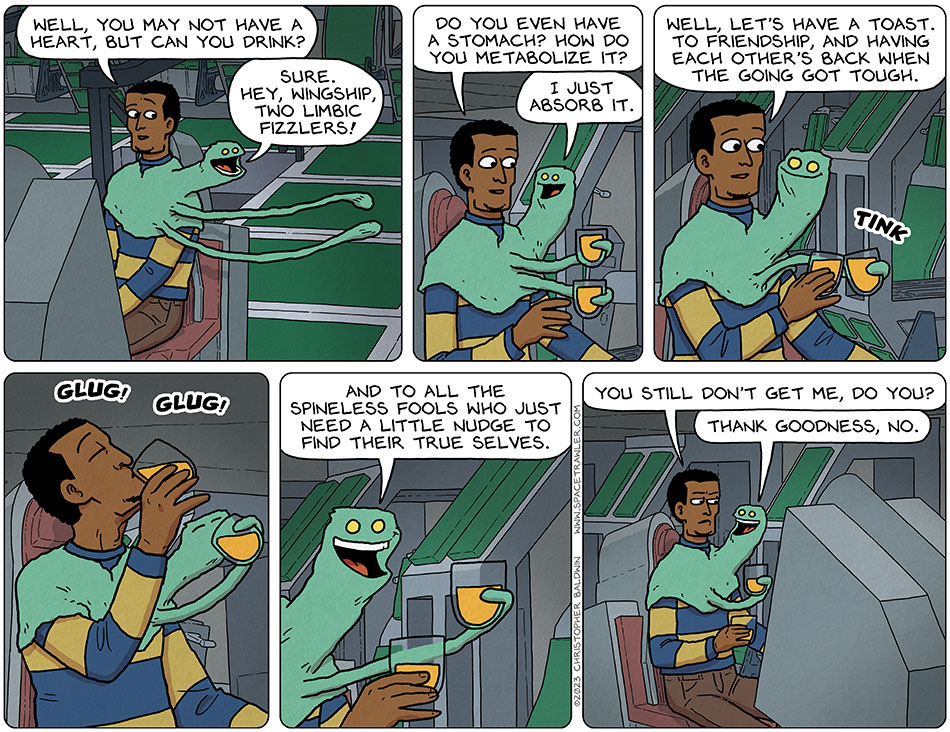

Spacetrawler, audio version For the blind or visually impaired, July 10, 2023.

Even with very good friends, sometimes there are some mile-high walls which will never be breached.

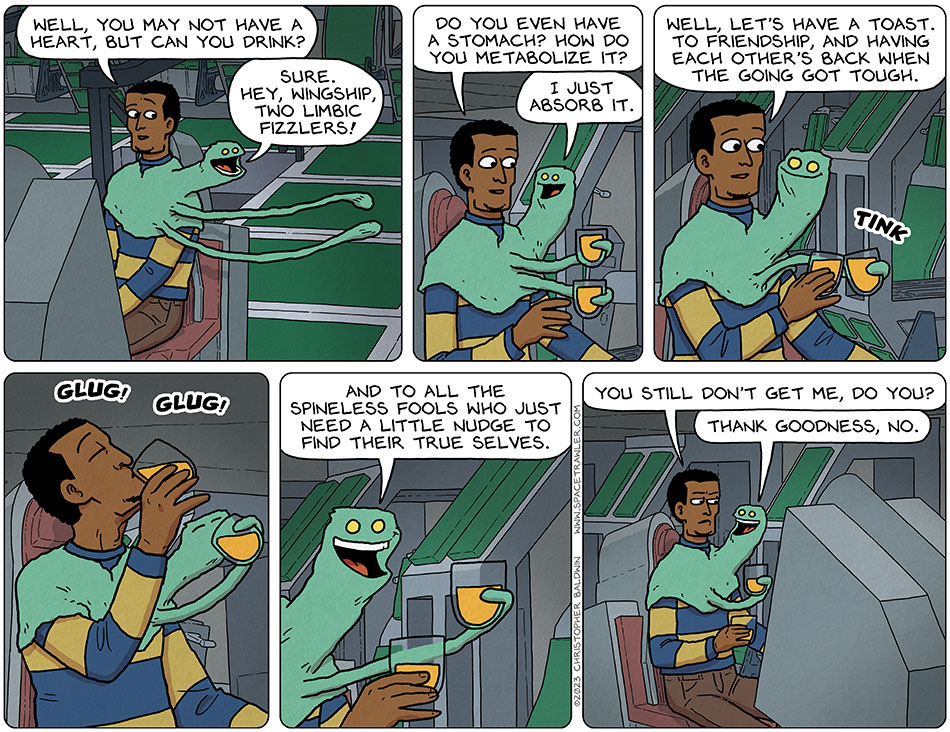

Spacetrawler, audio version For the blind or visually impaired, July 10, 2023.

Even with very good friends, sometimes there are some mile-high walls which will never be breached.

I’m not lonely. I’m very happy puttering around by myself and going out alone to enjoy things without the distraction of a companion. Yet people who see me “keeping to myself” keep trying to “help” me and console me. I don’t “just need a little nudge,” I need people to stop bugging me. The only pity party I’m interested in is Puddles’.

I’ve always been a loner, two. I got along with the other kids and would happily join them when I could, but being alone didn’t bother me. I could always find something to do. Now I’m old and living alone again after almost 50 years. I still find plenty to do.

There’s a difference between being alone and being lonely. A good deal of the latter spend inordinate time trying to change the former, and don’t understand what they’re doing wrong. No real changing them, I’m afraid. Just smile and tolerate them. They mean well, after all.

I’ve a friend who, alas, is a Second-Amendmenter of the first water. He believes an armed society is a polite society, and doesn’t understand references to Somalia or Sudan. His fantasy is unassailable and, to my way of thinking, not just unreasonable but demonstrably bonkers. He wouldn’t last a day in my old neighborhood, though he thinks he would do better than all right. No point arguing with him at all. Or letting him in my old ‘hood.

But I admit sometimes I’ve breached walls I shouldn’t have touched. Another friend of mine is a gifted scientist, and once a devout Catholic. I made the mistake of asking her one question one day, which I shall not repeat here. It broke her faith. She’s become something of a pagan, and seems happy about it, and I ask her no more questions. And we stay friends. Though the rubble at my feet makes me stumble sometimes.

Sounds like he has been reading too much Heinlein. The fully armed society sounds nice, but it would be far too easy to arrange hits unless you add some sort of system to insure no one abuses the system.

Kind of like the original premise behind communism. Sounds great, but requires super humans to work properly.

Early Heinlein was like that, ca. 1940, but after World War II and the postwar liberation movements he backed off that sentiment. My 2A friend has a purer vision, which he doesn’t realize is not just autochthonous, but solipsistic. He thinks because he imagines everybody around him will be armed and polite like he is, that’s the way things will stay. Heaven help the street he’s on if somebody hustles him for even a dollar.

Original Marxism had much the same problem, and did not take human emotions or motivations into account. Superhumans would not have made Marxism work — superhumans wouldn’t NEED Marxism. But if you postulate a struggle to replace a society with ordinary people with no real skills or understanding how a society works, and imagine then that they will develop a sort of autonomic socialism that provides for all needs, using all their presumed skills, you get a confused mob that needs to be told what to do and punished if people don’t obey. The Bolsheviks, and Stalin in particular, understood that force was the only basis for government, whatever its label, and worked to eliminate all opposition to their rule. Hence the seventy years of economic failure, relieved only by a ready resort to violence. Marxism works no other way anywhere in the world, and will always fail this way.

This is what happens when you build your economics on a Romantic fantasy of how people actually work together, or fail to. It’s the phlogiston chemistry of economics.

His late work also had this in it. Woman walks, in “Sorry I’m late, got caught up in a trial. Somebody jumped the queue, someone else shot him.”.

They held a trial right than and there, found him innocent due to excessive provocation. The end. I suppose someone had to collect the body and notify his family.

Literally everybody was armed at all times.

And that story was self-parody. Something I became aware of only after Heinlein’s death was that his writing contained a lot of shadowed, shielded, or just passing references to subjects and social conditions not further explained. And often unacceptable to his wider audience. He did this from early on; “Revolt in 2100,” about an America that has fallen under a dynastic religious dictatorship, opens with a guard in the capital witnessing a group of kids harassing and eventually stoning to death a ‘pariah’ — no other description given. Not then, nor anywhere else in the book. Apparently a ‘pariah’ was someone immediately identifiable as not of general society, and deserving death in the street therefore. Given Heinlein’s origin story for the rise of the nation-ruling Prophet, and its heavy reliance on Southern fundamentalists, it becomes apparent that Heinlein’s ‘pariah’ very well was black. Nothing else in the story is like this passage. But it is still there. I think Heinlein was indicating then who the bad guys really were. But you had to be quick to catch it.

A lot of people find his later “Starship Troopers” a celebration of a militarized society. He’s taken, and still takes, a lot of heat for that conception. But if you read the story, there’s precious little discussion of what kind of government exists, its size, its ambitions, or who participates in it. Oh, yes, only those who have served the government (and not just as soldiers) can vote — but who are they voting for? In what elections? Supporting or opposing what policies? No info. Absolutely none. Though this society puts a high value on military adventures on other people’s planets and regular people don’t seem bothered by this, there are NO politics in “Starship Troopers.” Just the war against the Bugs and their allies, like the Skinnies. Notice that these racial enemies of Earth have no other names but racist tags?

Heinlein himself, in a rare 1971 interview, asked about what happened to the characters upon their return from the invasion of the Bug home planet, Klendathu, stated bluntly that they didn’t return. That the invasion was a failure. And the war would be lost by humanity. But he never wrote a book with an unhappy ending, so “Starship Troopers” ends just before the Battle of Klendathu begins. The real ending is not in the book. It’s left to the reader to figure out.

“Starship Troopers” turns out to be a rather savage denunciation of militarism for its own sake — a situation he saw America falling into with the Korean War, and the book was written just before the debacle that was Vietnam. He’s got his lead character, Juan Rico, describing the necessity for offensive war-making capabilities, stating baldly, “No ‘Department of Defense’ ever won a war.” Which ended up being prophetic. More people should be aware of this, I think.

“Time Enough for Love,” his extended history of the near-immortal Lazarus Long (born Woodrow Wilson Smith, 1912), includes a section about a controlled ostensibly capitalist economy in a new colony on a distant world. The growth of capital is strictly limited so that while nobody starves, nobody gets rich either. Every piece of currency is tracked in a paper ledger (you can do that in small-enough settings) and the excess showing up is burned. Doesn’t go back into circulation for somebody to accumulate by whatever means. Individual effort is rewarded, inspiration and invention ditto, but the state — e.g., Lazarus Long — determines how well everybody will be doing. I don’t think anybody’s ever compared Long’s solution to that of classical Marxism, but it seems to me they have the same end — from everyone according to their ability, to everyone according to their need. I have to wonder if anybody denouncing Heinlein as a warmonger has ever considered that.

Heinlein publicly discarded a lot of early ideas of his. The heavily-populated rolling roads of “The Roads Must Roll” became discarded ruins in his later books. Most famously, in the short story “Gulf” he postulated a group of super-spies whose extraordinary abilities were realized through the then (1940s) popular idea of Renshaw conditioning, in which the unused assets of the brain could be stimulated into activity. The chief of these spies was one Dr. Hartley M. “Kettle Belly” Baldwin, and a master of hidden brain strengths. A much older version of this character shows up in the much-later novel “Friday,” whose eponymous heroine was genetically engineered to have superior capabilities, physical as well as mental, with no extraordinary training required. “Kettle Belly” has to finally admit near the end of the book that Friday’s kind of genetically-enhanced human is the real future, for which he and his training weren’t so much a precursor as a distraction. It’s the closest Heinlein ever came to admitting he was wrong.

But he wasn’t wrong with “Starship Troopers.” The novel’s a bleak and strangely dark parody of what happens to a society that militarizes when it encounters — surprise, surprise — another species that has bred an entire race of superior warriors who don’t need lengthy training or Mobile Infantry powered-armored suits to beat the tar out of humans. But the entire book is concealed as a story of humanity fighting an interstellar war, and one young man’s journey from bystander to officer in the Mobile Infantry. And that disguise fooled millions. Tens of millions, perhaps.

So I’m not surprised that minor acts of self-parody like the story you relate — which, I believe, also comes from “Friday” though I haven’t checked — get past you. Heinlein doesn’t write like somebody trying to trick you. He’s plain-spoken and direct. Only later, if you pay attention, do you notice the things he didn’t say, and the way the second telling of a story or a story element doesn’t quite match the original. We’re not taught to consider Heinlein a subtle author. But we should be.